Mental Health Problems and Stress: the epidemic targeting high schoolers today

As A’s become the average, high schoolers are suffering under the weight of hefty expectations; causing mental health problems and stress.

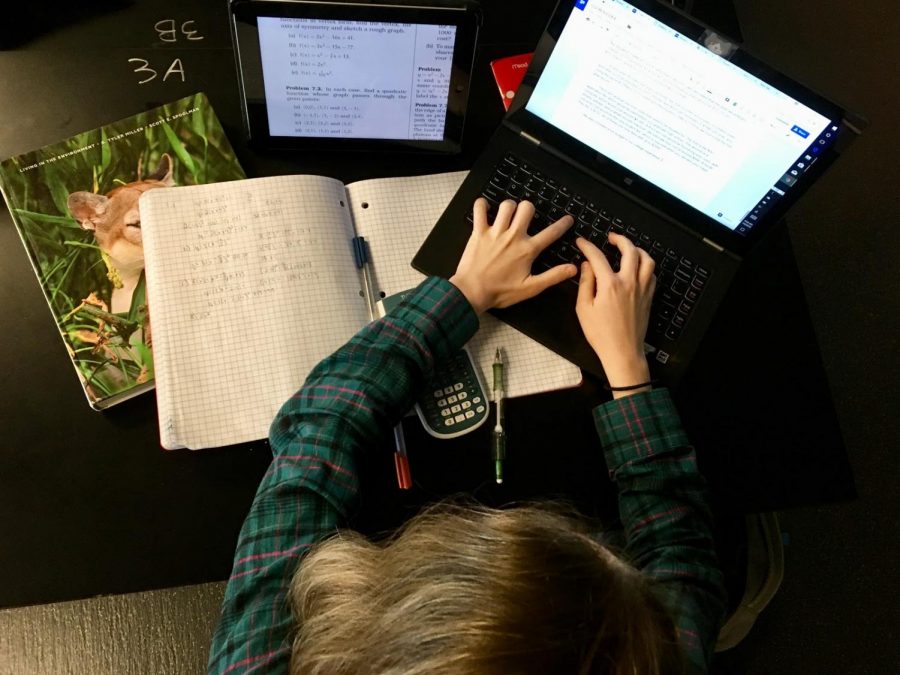

Students all over the country manage excessive amounts of homework in order to reach elusive “success.”

Parents of this generation may look back fondly on days when a C was deemed acceptable and A’s truly were top-notch. Yet, today’s high schoolers are living in a much different world; one where they aren’t expected to be good or even great, they’re expected to be perfect. The weight of these expectations is a heavy burden for young people to carry; causing stress, anxiety, depression, and other mental health problems. So the question arises: what is the effect of such pressure and how can we fix it both here at Shorecrest, and across the country?

Mental illness is upward trending in high schoolers. According to LiveScience.com, 1 in 5 teenagers suffer from a mental illness. In a survey of Shorecrest students, 50% indicated that they had a mental health illness, 88% of which noted that school at times exacerbates their already difficult mental health problems. School is not always the cause of these issues, but the stress education puts on a “normal” student is often too much for those with abnormal circumstances, such as mental illness, to handle. We as a school need to reduce the stigma around mental illness and search for how we can avoid the increase and/or creation of mental health problems in our student body. Anxiety, depression, and other disorders are serious, real, and common. They make everyday life difficult for sufferers and often make completing work grueling, if not impossible. We as a society need to adjust our education systems to work for all students and lift the burden that triggers mental illness.

The root of the problem is the societal expectations we hold for teenagers to excel. Every year seniors pine over dream colleges and worry about their chances of acceptance. That anxiousness has trickled down to freshmen and sophomores worried sick over having the right combination of good grades, extracurriculars, sports, and clubs. “There’s always articles in the newspaper about how much college costs, and how competitive schools are, and how many applications they get,” said Shorecrest counselor Wendy Friedman, “it adds this unnecessary pressure for kids to strive for this perfection so they can compete.” It will take time, but we need to help students and their families to see that high schoolers are not actually required to have 4.0’s and play three sports to attend universities. According to PrepScholar, the average GPA for college acceptees is a 3.0. However, many lower tier schools will still consider grades as low as a 2.0. Even admission to the top universities sometimes only takes a 3.5 GPA. Similarly, college is not the only way to go. “There are many different options out there,” said Friedman, “and 4-year college is not the only pathway, there are different options and kids need to figure out what’s the best thing for them.”

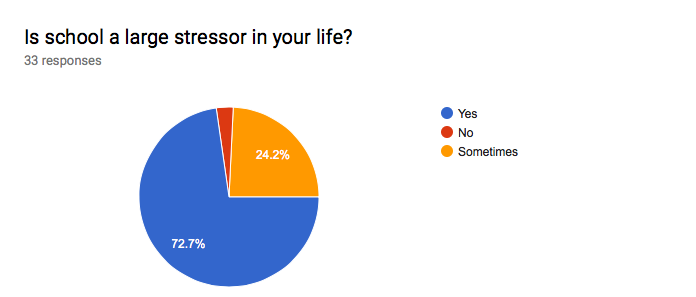

Most of our student body feels that school is a large stressor in their life. While 50% say that they have a mental health problem, clearly the negative effects go beyond just those with mental illnesses.

The prospect of college breaks down into everyday stress over doing everything correctly in order to achieve expectations. Often enough though, the bar is set so high for students that their ideas of hard work and perfection get blown out of proportion. It all starts in the classroom. In a survey of Shorecrest students, 72.7% stated that school is a large stressor in their lives, while 24.2% stated that school was sometimes a bother to them. “The pressure put on students to be ‘perfect’ in school is outstandingly high,” said Shorecrest senior Katie Evans, “it breaks my heart to see my friends having breakdowns and crying over a low test grade or some missing assignments.” She’s right, 84.6% of students listed homework or tests as being the most stressful part of their education.

The problem is that we as a society place so much value on numerical indicators of success that we fail to make sure students are actually learning. If the point is education, we need to turn away from the use of harsh grading that only discourages students and lean towards other more effective methods of teaching and assessing. “There should be more focus on if the kids are actually learning and enjoying themselves and getting something out of the class,” said Evans, “often there is so much pressure on acing tests and turning in all of the homework that I find myself learning nothing in the class itself, because I’m too stressed.”

BachelorsDegreeOnline.com actually found that less serious and more creative based homework assignments such as writing songs or making videos on a topic worked just as well as the monotonous memorization and recreation of facts we so often see in classrooms across the country. Not only that, but it can be argued that that kind of work promotes the actual learning and application of a subject, not just regurgitating on test day and then forgetting. “I know in countries that are said to have much better education systems, they put a larger emphasis on actually learning, and the students learn what they’re interested in,” said Shorecrest senior Aldo Chavez, “and if that were the case, I think that would make students much more interested in school, which would make them do better.”

Many teachers argue that the kind of workload they are forcing on their students is in preparation for college and ‘real-life.’ However, statistics show that teens are more stressed out than adults (people who are actively dealing with ‘real-world’ stress). NBC provided a ten-point scale on which ten was the most stressed and one was the least. It showed that while adults rank themselves around 5.1 in their day to day lives, teenagers put their stress levels at 5.8. While it may seem that teens are just being more dramatic or attention seeking than their adult counterparts, the same study stated that high schoolers seem to downplay their problems; 52% claiming that stress had little to no effect on their mental health versus 43% of adults. If teenagers were simply looking to exaggerate their situations, a majority of them wouldn’t be saying they were unaffected by their stress. Mental illness and pressure seem to be so ingrained in the lives of young people that they can hardly separate them.

Many may not realize just how much work our high schoolers are putting in. USANews detailed that most high schoolers in the country have on average around 17.5 hours of homework per week. This means that on top of a seven hour school day, students add another 3.5 hours of work each week day (though many still work through the weekends), making their work day upwards of 10 hours. This culminates in an estimated 50 hour work week. Of course, this is a generalization and the numbers don’t advocate for the large amount of students who have AP classes, hours of sports practice or rehearsal each day, or who have their own part-time job outside of class. Many students have so many responsibilities they can barely find time to hang out with a friend, watch an episode of a TV show, or work towards goals other than academics. Our teenage years are incredibly important to our growth as members of society and require us to branch out socially, take care of ourselves and our health, and enjoy life.

The workload teens experience is usually more than will be expected of them as adults or in college. There is a fallacy that when we enter ‘real-life’ no one will be there to help us, no one will cut us slack or give us a break, and that we will have to work around the clock to achieve greatness. This idea is simply not the case. Instead of scaring teens, we need to foster their growth and arm them with valuable skills such as communicating, critical thinking, application of ideas, and hard work. Knowing how to flip flashcards or strategically guess our way through multiple choice tests will not do anything for our futures. How often in a job will we be forbidden to look at information we forgot, unable to go back and fix a mistake we made, or have our work judged on a strict scale? If the school system wants to prepare students for the real-world, then it needs to allows students to practice real-world skills.

Where are we headed with this? The problem is already edging on dangerous. There is literally no more time that can be taken away from high schoolers. The education system cannot continue its current trajectory. If it does, we as a society risk the lives and well-beings of our youth. Students are already working through meals, and growing accustomed to four hours of sleep. Change has to happen, and it has to happen now. Imagine where we’ll be if we can’t find a way to relieve teenagers’ responsibilities.

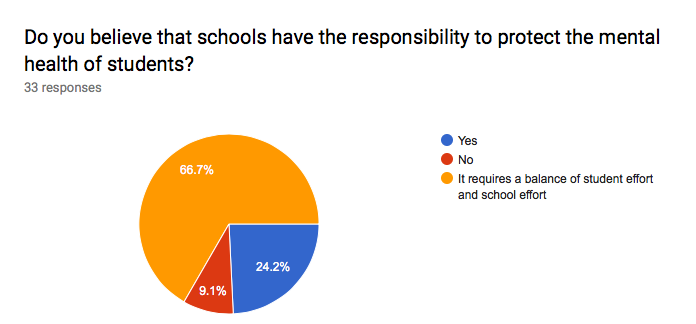

Over 90% of students feel that schools should take some amount of responsibility for the mental health of the student body.

So what do Shorecrest students want changed? In the survey, several students mentioned a desire for teachers to be conscious of how much work they are really assigning, an increased focus on learning during classes, and better communication between teachers so that due-dates do not collide. Obviously there is no short and sweet way to fix the problems with our school system. Just like students cannot be perfect, our education system can’t be either. However, with so much evidence being shown that school is having a negative effect on many teens’ mental health, something has to be done and it starts with distribution of information. By spreading the knowledge that 90.9% of Shorecrest students believe that our school has the obligation and responsibility to aid in the protection of mental illness, we can build a safe space for all students.

We already have some systems in place to help students deal with mental illness and stressors. Natural Helpers, led by teachers Marcy Caruso and Lacy Clark, is “a program where students identify their peers who are already people who they go to for help,” said Caruso, “those students [are trained] to be able to support their friends better and to take better care of themselves, and be more visible in the school, and also support people who are in times of need or crisis.” Trained through an overnight retreat in the fall and once a month follow up trainings, these Shorecrest students are specifically there to help others and are a great resource to use. “They would love to have others reach out to them,” says Caruso. Their information is on the third floor bulletin board near the math wing.

As a teacher, Caruso has implemented great strategies to limit stress and anxiety among her students. “We try and teach the students how to prioritize things,” she explains, “how to advocate for themselves and ask for help when they need it, and then try to teach good behaviors that will help them destress when possible.” Her main tip for fixing the rampant mental illness problem in American high schools is to “just be a listener.” Many who suffer mental illnesses feel emotions that seem irrational to others, which is one reason why teachers may not always see the effect their classes have on students. “What [students] really want is to be heard and validated. And no matter what that person is feeling,” said Caruso, “feelings are valid and legitimate, and it doesn’t matter if you think [it’s] a rational feeling, if that’s how the person is feeling then we have to deal with it.”

We also have counselors at Shorecrest who are always willing and open to support the needs of students. Similarly, students can contact TeenLink, an outreach program led by teens that anonymously helps others their age through hard times. Their number is (206) 461-4922. Of course these responsibilities do not fall solely on the shoulders of the school. Students and their families are equally accountable for getting teens the help that they need and encouraging the healthy management of stress. However, the initiative has to come from the education system.

So what do we need to do? First, let kids know it is okay to take a break and not do it all. “[With] the kids who we really see that have a lot of anxiety, [the problem] can be more about the need to be perfect,” said Friedman. The school system is meant to push kids to reach their potential. This is often to encourage those who have chronically low grades and sub-par work ethics. However, the pressure that is meant to be felt by those who need an extra push is often felt mostly by those who are already at the top. The expectations students have for themselves on top of whatever mental illnesses they may be dealing with that makes them strive for perfection, leaves these kids teetering on the peak of a mountain so slippery they might just fall if they try to climb any higher. Students (and teachers) need to realize that faults are unavoidable. “Even a 4.0 student who goes to Harvard on a full-ride scholarship,” explained Friedman, “even that person is not perfect, and everybody makes mistakes and learns from mistakes, and I think that we all could benefit from [giving] yourself a break.”

Second, we need to adjust what we are teaching students. Teachers should think about if their material is important and relevant to real-life, and if the type of assessments they are using are fostering the development of valuable skills. Teenagers should want to come to school and learn. They should be excited by the prospect of gaining knowledge and participating in fun activities. “School should be a place where we go to learn and find out what we love to do,” explained Evans, “not a competitive, toxic atmosphere that puts mental health at stake.”

Third, teachers should be aware of the fact that many of their students are dealing with mental health illnesses that make homework extremely challenging. At Shorecrest, that number is about half of our student body population. By focusing energy away from assignments and towards in-class learning, we can minimize the negative effects of homework on teens.

Finally, remember that school is meant to guide us into the world, not shove us into it. The way we are running our education system in this country is at fault. Students have been crying in bathroom stalls over test grades and suffering panic attacks over one too many homework assignments for long enough. We are (and have been) raising our voices about what we need, and it is time for the education system to start listening.