The Greatest Film Never Made: Jodorowsky’s Dune (Part Two)

Part Three: Spiritual Warriors

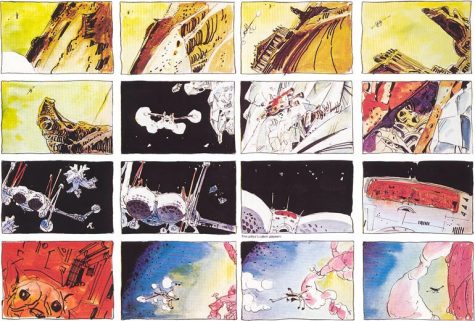

Alejandro Jodorowsky himself has two separate stories as to how he became interested in Dune as a film. The first comes from an interview in the French Metal Hurlant magazine. He claims that he was spiritually ordained in a dream to make the film, not an unusual claim for Jodorowsky. He then went out and bought the book after waking up and, most unbelievably, read it in one sitting. In the documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune, he tells a different story. A friend had told him that Dune was good, so he said he wanted to make Dune. Either way, history was made. Jodorowsky began working on a screenplay soon after and began assembling his team. First up was Jean Girard, known in the comic book world as the artist Moebius. Girard had been drawing covers for sci-fi books, as well as western cowboy comics. Jodorowsky commissioned him to create a full storyboard, as well as several concept sketches. While the full storyboard isn’t available, some have been released online, as well as several of the concept drawings. Overall, Moebius completed over 3,000 drawings for the project.

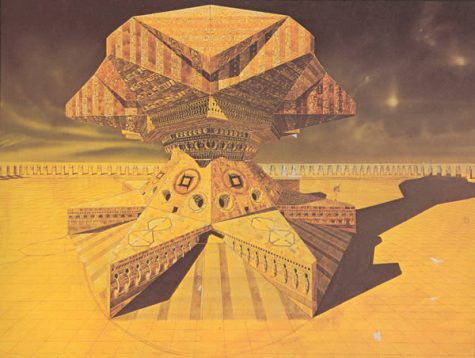

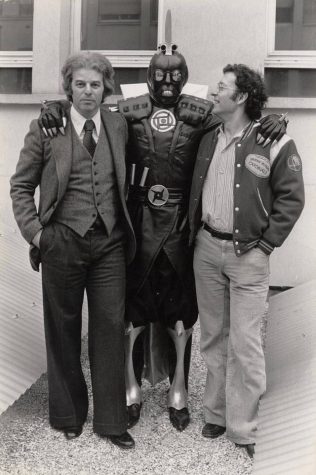

Next, Jodorowsky needed to find someone to create the special effects for the film. The Moebius storyboards show things that had never been done before on film. This was several years before Star Wars, and Jodorowsky had planned things that we are seeing for the first time in movies now. He wanted his spaceships and vehicles to act as if they were alive, and move in a flowing, loose sort of way. The planets and buildings were massive and incredibly detailed, and the costumes were extremely elaborate. He wanted the opening shot to be a long continuous shot traveling through the universe before finally reaching Dune, and he wanted the last shot to be the planet transforming into a forested green planet that leaves the galaxy. These effects were so extravagant (and possibly expensive)that Jodorowsky needed to find a genius to attempt them. He first met with Douglas Trumbull, the mastermind behind the effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey. Apparently, Trumbull was on board, but Jodorowsky didn’t end up hiring him because he “wasn’t spiritual enough.” Jodorowsky was interested in making a spiritual journey for the audience, and Trumbull was just interested in making a movie. He then went to see a film titled Dark Star, directed by film student John Carpenter (The Thing, Halloween), with special effects by another film student, Dan O’Bannon. Dark Star was filmed on a budget of $60,000, and it looked really, really good. Jodorowsky called O’Bannon and described his vision for Dune. He was immediately hooked. He packed up everything he owned and moved to Paris to start work. Sci-fi book artist Chris Foss was the last of the main artists to be hired to work on the film. He was brought on to design all of the spaceships and vehicles for Dune, a massive responsibility. According to Jodorowsky, “Every spaceship was a being, like an insect, like a fabulous bird.” With that guidance, Foss set to work too. These artists, Moebius, O’Bannon, and Foss, now living together in the same hotel in Paris and working in a rented office building, were Jodorowsky’s “Seven Samurai,” or “Spiritual Warriors.” They weren’t making a movie, they were fighting to create something so profound that it would change the world forever.

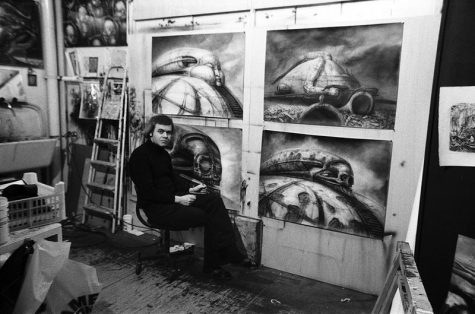

The last artist didn’t move to Paris to work with everyone else, but was still a huge part of the design process. H.R. Giger, a Swiss artist who was gaining prominence in the art world, was contacted to design the dark and mechanical world of the Harkonnen homeworld Giedi Prime. Each planet was going to have not only its own look, but its own music as well. French prog-rock band MAGMA would have composed the music for Giedi Prime, and Pink Floyd would have composed the music for Arrakis, as well as most of the soundtrack. It was not unusual for Pink Floyd to do film soundtracks at that time. They had worked on the French films More, La Vallée, and the American film Zabriskie Point. Jodorowsky met with them at Abbey Road Studios while they were recording Dark Side of the Moon, and they agreed to work with him. Other musicians in talks to create music for the different planets included Gong, Mike Oldfield and Tangerine Dream.

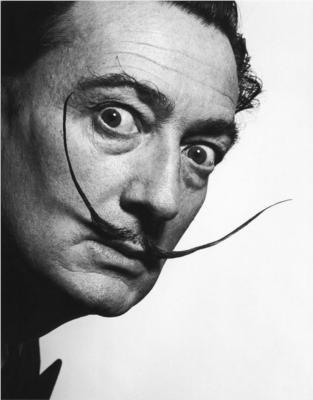

Now we come to the cast, perhaps the craziest part of the entire project. First, there was Brontis Jodorowsky, Alejandro’s son, who would’ve played the lead character, Paul. His father put him through months of daily martial arts training to prepare for the film, months that Brontis now says were some of the most difficult in his life. David Carradine and Geraldine Chaplain would have played his father and mother, and Alain Delon would have portrayed his bodyguard Duncan Idaho. Orson Welles, of Citizen Kane fame, would have played the rival house baron Vladimir Harkonnen. Jodorowsky describes how he met Welles at a restaurant and tried to convince him. After originally saying no, he had agreed once Jodorowsky had offered to hire the chef of the restaurant to cook for him every day of the shoot. Rolling Stones lead singer Mick Jagger, who apparently approached Jodorowsky and agreed immediately when offered the part, would have played the Barron’s protege Feyd Rautha. Finally, and most famous of all, the Mad Emperor of the Galaxy would have been portrayed by surrealist painter Salvador Dali. Dali had some pretty insane demands. He wanted to personally design his throne, asked for an upside-down burning giraffe in every scene with him, and, most insane of all, he wanted to become the highest-paid actor in history with an outrageous $100,000 per hour salary. Jodorowsky said yes to all of his demands, and rewrote the script so they would be able to shoot all of Dali’s scenes in one hour. Now he had his cast, his artists, his special effects, he had a completed script and storyboard, as well as plans to shoot 70mm film on location in Algiers. So, what happened?

Part Four: The Collapse

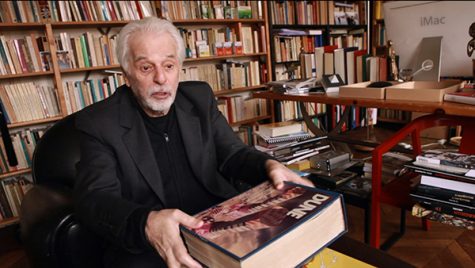

All that we know for certain is that production paused for a Christmas break in 1975 and never returned. Jodorowsky needed money for his project. They had spent $2 million in pre-production alone, and budget projections ranged from $9-20 million. He compiled all of the pre-production work into one massive “Dune Book,” and sent copies of it out to every major US studio. They all declined to back the project. There were two major reasons: one was that big-budget sci-fi films were considered to be unprofitable and that they didn’t have an audience. Planet of the Apes was considered by studios to be a strange fluke by the studios. The writing was excellent, special effects and makeup were great, and the story was interesting and compelling, but it was still a sci-fi film about talking apes. Meanwhile, Kubrick, who created 2001: A Space Odyssey, was able to make a profit off of any film he made just because his name was on it. He was a genius, perhaps the greatest filmmaker of all time, but one of his greatest strengths was his ability to work with the studios to get the funding and get his projects made. This was the second reason why it wasn’t picked up: Jodorowsky was a risky director. He was difficult to work with, and studios were worried his imagination would get in the way of reality. When asked how long his movie would be, he would frequently say that it would be as long as it needed to be. When pressed, he threw out numbers like 3 hours, 10 hours, all the way up to 14 hours. According to Seydoux, the script alone was long enough for an 11-12 hour movie, and was the size of a phonebook. Jodorowsky’s previous films were also definitely not appropriate for a major audience. So that’s it then? Jodorowsky’s Dune was too expensive and too inappropriate to be made? Well, maybe not.

According to Giger, Jodorowsky had discussed his frustrations with censorship and his movies. He claims that Jodorowsky said he was going to cut all of the nudity from the film so more people would be able to see it. His goal was to change the world, and how could he have done that if no one would have been able to watch it? Another limiter on Jodorowsky’s wild imagination was Moebius, who refused to draw some of the more violently graphic scenes in his storyboards. So, if it was appropriate for audiences, was it the budget that was out of control? Again, maybe not. Dan O’Bannon was hired specifically because he could create realistic visual effects for a fraction of the price usually needed. Seydoux also said that there was a budget cap at $15 million. While that might sound like a lot, in film terms, it’s relatively reasonable. Cleopatra, made in 1963, cost between $30-40 million, the most expensive film of the year, The Towering Inferno cost $14 million, while 4 years later in 1978, Superman was made for $55 million. As for the length of the film, Seydoux claims in the documentary that they had agreed on a 2.5 hour runtime, not quite the 10-14 hour epic Jodorowsky had planned. They also had the full backing of Seydoux’s French production company. All they needed was a US distributor to put up $5 million for the film, as the film wouldn’t have been able to make a profit in France alone. But again, Jodorowsky’s perceived audience wasn’t as broad as the studios needed, and they declined to pay. The film went from being one of the most ambitious projects ever attempted to just another failed production by a director ahead of their time. But it still left an enduring legacy, one that is sprinkled across almost every other science fiction film after it’s demise.