The Problems with Turnitin

At the beginning of the semester, one of my teachers informed our class that we would be submitting our papers through a website called turnitin.com. Basically, you submit your writing to the site, and it then compares your paper to a database of other sources on the internet (as well as previously-submitted student papers) and produces an Originality Report to show how much (if any) of your paper was plagiarized. Sounds useful, right? I thought so too. So when someone I know started complaining about the problems with Turnitin, I thought they were just overreacting.

And then I started researching.

It turns out that Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and Stanford have all actively decided not to use Turnitin. Four high school students sued the company in 2008 (and lost, because they technically agreed to the privacy policy). In addition, the Canadian Federation of Students took up a position against it. So what’s the problem with Turnitin? Well, there are a few.

First of all, it presumes guilt on behalf of the students. How many students at SC would actually plagiarize their papers? I don’t know, but I know that I would never do that, and I don’t like that my teachers are implicitly assuming that I would. In the lack of actual statistics, however, I will concede that it’s quite possible that students might plagiarize, and that teachers want to prevent that possibility.

But does Turnitin prevent plagiarism? Several studies have shown that it actually doesn’t do a great job. It has a surprisingly high rate of both false positives and false negatives. In 2015, Dr. Susan Schorn, Writing Coordinator for the School of Undergraduate Studies at the University of Texas, submitted six essays consisting entirely of unoriginal text to Turnitin. Turnitin missed 44% of the sources. (She did a similar test earlier, in 2007, and got similar results, with the added discovery that simply searching three to five words in Google did a much better job of finding sources than Turnitin.)

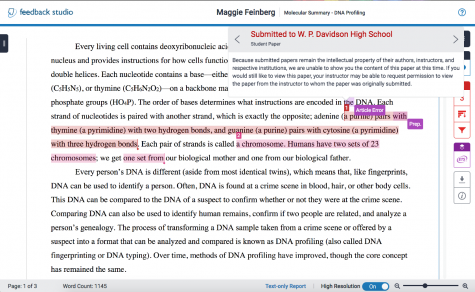

In 2009, professors at Texas Tech University submitted 400 student papers from their database to Turnitin and analyzed a subset of the papers more closely. They found that Turnitin frequently flagged things that weren’t actually plagiarism but instead composed of commonly used phrases. (I noticed this in my own paper, where Turnitin flagged the sentence “Humans have two sets of 23 chromosomes.” Um. What?)

Furthermore, many students take issue with the fact that Turnitin effectively takes students’ papers and profits off of them. When you submit a paper to the site, it’s added to their database where future papers are then compared to for plagiarism. This database is a paid product, and it utilizes our papers, which means that it is profiting from our work.

Once your paper is added to their database, they may even share that paper with other teachers if it flags as similar (as some papers submitted to W. P. Davidson High School were flagged in my paper). This is potentially copyright infringement, and this was the subject of the aforementioned suit in 2008. Turnitin won the suit because users of the site technically agreed to this when they clicked the little “I agree to the Privacy Policy” button… but let’s be real, does anyone actually read that? And if you did and you had a problem with it, would you even have a choice to not use the product? (I’ll note here that someone in my class did have a problem with Turnitin, and the teacher agreed to let them submit their papers via email rather than the site.)

But if no one reads the policy, and no one does any digging–after all, it’s just a site your teacher requires you to use a couple of times a year; it shouldn’t matter–we are then letting the company get away with anything they want. First Turnitin, then what? Are companies going to be selling our personal data without us even knowing or caring? Oh, wait! That already happens!

There are so many companies whose products we can’t feasibly opt-out of, like Google or Facebook, or Apple. I mean, sure, you can if you try really hard, but they’re so ingrained into our society that it’s extremely difficult. Turnitin isn’t one of them.

Why are we going along with a site that profits off our work, isn’t very good at what it claims to do, and isn’t necessary?

Now, if any of the teachers that use Turnitin read the Highland Piper, at this point they will probably start to protest. “But it’s useful!” they’ll be thinking. I do not dispute that there’s a reason people decided to use it in the first place, nor do I presume to know everything going through a teacher’s head when they make the decision to use a service like Turnitin.com. But perhaps the solution to plagiarism is not using a somewhat problematic website but monitoring students’ progress as they go, checking in with us, and if you have a feeling someone may have plagiarized, copying a few words into Google and seeing what pops up. In my opinion, it is literally more effective than Turnitin.

Darby O'Neill • Feb 18, 2022 at 11:06 am

SLAYYYYYYYYYY SO TRUE (-sw newspaper)