The Warrior Caste in America

Since the early formations of human society, there has been a sense of glory in fighting. For societies to triumph over others, they have needed people willing to lay down their lives for the goals of the state. This kind of governmental Darwinism has led to the most powerful societies in history being the ones who could exert power over others militarily. And to assert this power, they needed a population who was willing to give up their own lives for a cause, not necessarily one that benefitted their own lives and goals. The most powerful societies started taking steps toward creating the Military-Industrial Complex of today. In Ancient Greece, the Spartans became the backbone of power for the Greek city-states due to their commitment to militarism. In Hinduism, the “Kshatriyas,” or warriors, were second only to religious leaders in the caste system. In the 18th century, Prussia claimed to be a “military with a state” instead of vice versa, placing soldiers above civilians by law and would go on to form the German military culture that led to two attempts to conquer Europe and possibly the world.

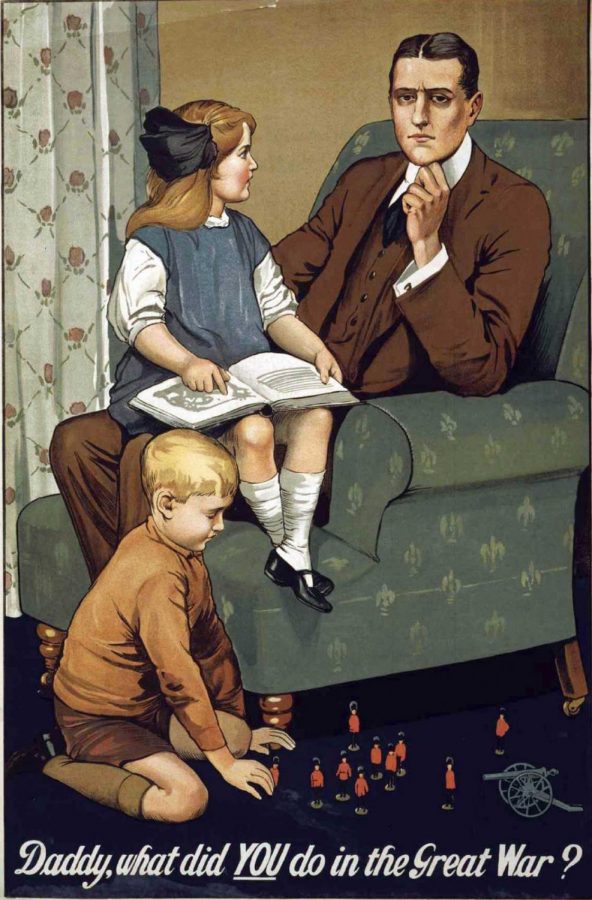

With this elevation of the military above other contributions to society, those who could not fight were considered a subhuman class in many societies. In Sparta, infants not deemed fit for service were abandoned to die. During WW1, British women were encouraged to hand out white feathers, a symbol of weakness and cowardice, to men who were not in uniform, regardless of whether they could fight or not.

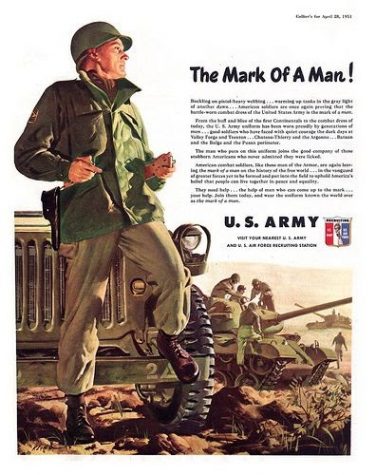

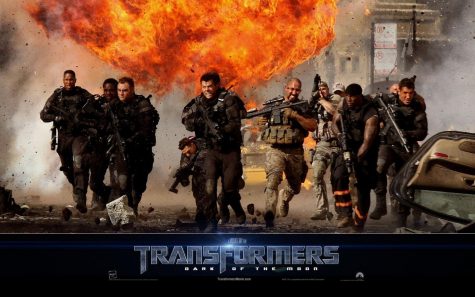

As a young man growing up in post-9/11 America, the tradition of military worship was alive and well. The politics of this renewed era of nationalistic fear branded anyone who was against the Iraq War or the military unpatriotic at best and traitors at worst. And I knew no better. The commercials at the time would advertise toys like Nerf Guns and portray kids as soldiers and war as a fun game. With their lucrative incentives from the Pentagon, Hollywood would constantly glorify the military in their media, even in the most unexpected places like “Mickey Mouse Clubhouse” (see also). The Pentagon would exchange funds and use military equipment for the promotion of their institutions. This led to movies like “Transformers” becoming well-disguised military recruitment propaganda targeting children. So much of what it meant to be an American or even a man, to begin with, was tied to fighting and militarism.

In elementary school, my friend and I would walk around the playground carrying sticks like guns, pretending we were soldiers on a battlefield, and talking about the glorious conflicts we would eventually fight in. We had swallowed the kool-aid hook, line, and sinker, and we were marching our way into the life-consuming machine known as the Military-Industrial Complex. As I grew older, my thoughts of war changed. I began to realize that what the United States was fighting for was not right and that war was a hellish experience, yet my ambitions didn’t change. I still saw the military as a fun adventure that would earn me the respect of my peers and help my future as an aspiring politician. I had seen it all around me. Veterans were constantly praised for their service, welcomed first onto airplanes, thanked before sporting events, and honored at school assemblies. Service was used as a credential in politics. I looked up to these people. Although I didn’t always agree with what they fought for, I saw their sacrifices as honorable and yearned for an opportunity to prove myself as a member of this selfless and noble warrior caste.

But when I became serious about joining, around ninth grade, reality began to set in. I had a host of medical issues that would present challenges to enlisting. I fought hard, researching loopholes, waivers, criteria, even having a doctor strike a potential allergy diagnosis from my medical records to make sure I could join one day. All the while, I built up the physical and mental strength required to serve. I pushed hard to get in shape through various sports and workout programs, with my ultimate goal of mental toughness giving me the strength I never knew I had. Eventually, I decided to back off from these goals due to a combination of my parents’ coercing, politics, and realization of the horrors of war. (The infamous opening scene of Saving Private Ryan may have contributed as well.) Yet, being a core part of my personality, this obsession remained in the background. I became an expert on military history, especially more modern conflicts like the World Wars. My favorite video games were shooter games, and my favorite movies were related to the military, like Star Wars, which ironically had a heavily anti-war message (see also), yet somehow I could not see that until later. My actual goal of joining the military disappeared but my obsession with military aesthetics remained strong as ever. I would often think of “excuses” to get that goal back one day.

For years I was able to live in that status quo. Through the crisis that would grip the world in years to come, I would still imagine myself as a soldier in a war. I would see my suffering as my duty to others and my struggle as something that would one day earn me the respect of serving. But one day, long after I had decided against serving, this status quo came crashing down. When randomly thinking one day about yet another excuse to join, it occurred to me that I had not checked all of my medical problems and when I did, I realized I had missed one. It happened to be an automatic disqualification, no waivers, no record changing: it was over. I sat for an hour in shock. I didn’t know what to do. Everything I did, how I acted, entertained myself, how I thought had been with this military mindset, and suddenly I felt like I no longer could identify with that. My government had flat out told me that I was unworthy of the warrior caste. Over the next few days, I slowly had to come to terms with my position. Everywhere I looked, I saw my old identity and wondered why I felt like I now inhabited a lower caste of society. In a way, I felt glad I had finally broken out of this ancient societal indoctrination, but it didn’t feel good by any stretch, for it was a baptism by fire. I began to try and search for a new identity. Finding a new career goal was not hard. After all, I didn’t want to join the military regardless, I had already wanted to go into politics. The hard part was changing my mindset. Regardless of my actual intent to join the military, I had always seen myself as a soldier of sorts, and now I was told I couldn’t be that.

And while my story is a single anecdote from a relatively privileged person, there are still other, graver consequences to military worship. Believe it or not, military worship actually harms veterans. As the media portrays soldiers as valiant heroes who are almost gods among men, they purposely leave out the negative effects that war can have on an individual. This leads to many veterans feeling like they have to hide conditions like PTSD or not even being diagnosed at all. (see also) This certainly contributes to the already high rate of suicide, depression, and addiction among veterans.

Another consequence of this cult of war is the functioning of the government itself. When military service is elevated to the ultimate or even sole way to serve your community, other positions suffer. The COVID pandemic has highlighted the many individuals who make sacrifices similar in importance and rigor to the community, like healthcare workers, farmers, teachers, and postal workers. Yet these positions rarely get recognition or due compensation, while the military basks in glory. If you question the military you could be branded as “disrespectful” or “unpatriotic” which has also led to the military getting special status as an organization. The military consumes a disproportionately large amount of the government’s budget to the point that there is no logical way it can do more good than harm. For example, the proposed military budget for 2022 is $753 billion. For the same price, we could provide universal child care, paid family/medical leave, universal housing, national high-speed rail, free college, universal internet, and 100% renewable electricity by 2030 and still have $6 billion left over. In fact, the price of a single aircraft carrier could house the entire homeless population of the US.

While this hyper-militarism has led to power in the past, we live in a different world. Since the end of WWII, nations have taken great strides towards phasing out conventional war. We are slowly moving towards an era where economics and diplomacy matter more than brute strength. The rule of the military has existed for thousands of years, but so did slavery and other institutions that we as a society have progressed beyond. Wealthy nations like Switzerland have not engaged in war in hundreds of years, and Iceland, the happiest and most peaceful nation on earth, has no military aside from a small coast guard, with many other states possessing little to no armed forces. If nothing else, the US spends more on their military than any other nation, and a reinvestment of those funds back into our nation would greatly improve our crumbling infrastructure and rising poverty and accomplish feats such as eliminating homelessness that is deemed impossible in our current political climate.

But to accomplish such a simple yet momentous task, we must break the myth of military supremacy. If we continue to worship the military as a pseudo-divine ruling caste, our society will inevitably be violent and unequal. Society has progressed beyond the need for this practice and now does more harm than good. I’m not saying that veterans should not be commended for their sacrifice, but treating them like gods among men only harms society. As weapons become more advanced and the process of killing becomes more efficient, the need to do away with war culture is necessary for our very survival. As echoed by the words of John F. Kennedy, “Mankind must put an end to war, or war will put an end to mankind”.