The Female vs. Male Gaze in Cinema

Little Women (2019) was a recent and popular example of the female gaze. From left: Emma Watson as Meg, Director Greta Gerwig, Saoirse Ronan as Jo, and Florence Pugh as Amy

Introduction

Over the summer a trend on TikTok began to surface- girls or people who weren’t cis, straight, white males would ironically pose in a provocative position with the song “Glory Box” by Portishead playing in the background. The lyrics would sing, “for I’ve been a temptress too long” and the captioning would say something like “POV I’m an (insert personality archetype) written by a man”. This trend brought a wider discussion about how women and other marginalized groups are portrayed in media and the popularization of terms such as “male gaze” and “female gaze”. What is the difference between a male director’s perspective and a female director’s perspective? Is the male gaze even real? How do POC and LGBTQ people fit into this quite binary set of labels?

Over the summer a trend on TikTok began to surface- girls or people who weren’t cis, straight, white males would ironically pose in a provocative position with the song “Glory Box” by Portishead playing in the background. The lyrics would sing, “for I’ve been a temptress too long” and the captioning would say something like “POV I’m an (insert personality archetype) written by a man”. This trend brought a wider discussion about how women and other marginalized groups are portrayed in media and the popularization of terms such as “male gaze” and “female gaze”. What is the difference between a male director’s perspective and a female director’s perspective? Is the male gaze even real? How do POC and LGBTQ people fit into this quite binary set of labels?

What is the male gaze and how has it been the norm throughout the history of cinema?

“The Default Male gaze does not just dominate cinema, it looks down on society like the Eye of Sauron in The Lord of the Rings. Every other identity group is ‘othered’ by it.”

― Grayson Perry, The Descent of Man

The male gaze was a phrase coined by British film theorist Laura Mulvey. The feminist film theory describes it as the act of depicting women and the world, in the visual arts from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer. What are some signs that the movie you are watching might be in a misogynistic perspective? Some symptoms of the heterosexual male gaze may be predominantly male writers, directors and cinematographers, an exhaustive amount of nude female characters lacking the same amount of exposure when it somes to the character depth, panning of camera and zooming in on certain sensual parts of body, focus on legs, bottoms, breasts and stomachs instead of eyes, body language, or other signafiers of deeper levels of thinking.

In the shot from Transformers, notice where the camera is focused. Its objective is not to show internal conflict or character depth. The main focus is on her torso and it is hard to see any facial expressions.

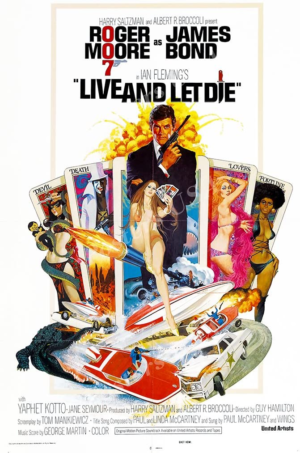

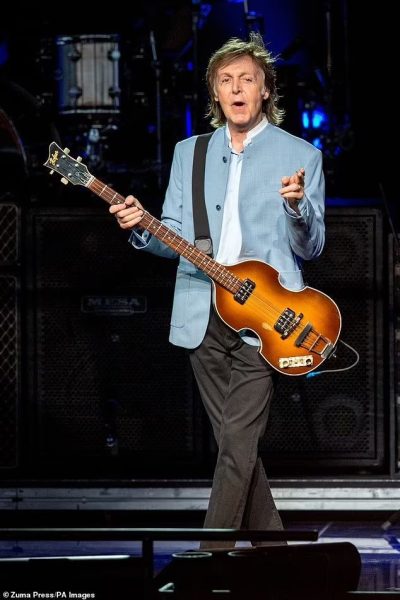

In the cover of Live and Let Die, notice how the man is portrayed in contrast to the women. The women seem to be inconveniently having to roam around in their undergarments while James Bond gets to cover his tighty whiteys with a fancy suit. Maybe there was a fabric shortage on set and they could only afford to suit up 007… But judging by the fact that they got a literal Beatle to write them the bop that is their title track “Live and Let Die,” I think the lack of clothing was more of an intentional choice.

So what’s the problem?

According to research done by Dr. Martha M. Lauzen and The Center of Women in Television and Film, the percentage of top-grossing films with female protagonists dropped dramatically from 40% in 2019 to 29% in 2020. Women are just not able to see themselves on screen as much as men. Another scary statistic was that Women only comprised 16% of directors working on the top 100 grossing films in 2020, up from 12% in 2019 and 4% in 2018. This is technically progress, but these numbers are still low and depressing.

“What are other women really thinking, feeling, experiencing, when they slip away from the gaze and culture of men?” – Naomi Wolf

So what’s the female gaze?

The female gaze is a response to Laura Mulvey’s coining of the term male gaze. It is a feminist theoretical ideal of how or if a movie could be shot from the perspective and from the perspective of the female viewer. It showcases feminity outside the typical heterosexual male perspective seen in film today and throughout history, avoiding objectification and shallow characterization. It typically focuses on parts of the body linked to internal conflict such as eyes, body language, and facial expression rather than the predominant angles on breasts and legs seen in typically male-gazed films such as the ones in the examples above.

Little Women, 2019, directed by Greta Gerwig

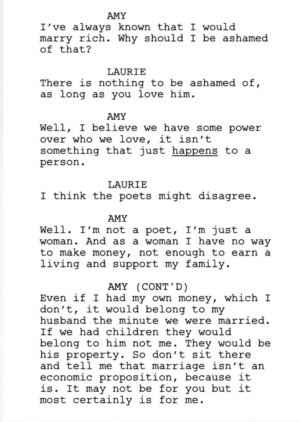

One of the most recent and popular examples of the female gaze was the latest adaptation of Little Woman, directed by Greta Gerwig. The film has many complex female characters with their own motivations set outside of men. What I believe this film did most incredibly was add complexity to the character of Amy March, portrayed by the wonderful Florence Pugh.

Instead of villainizing her femininity and conformity with her restrictive society, the film shows her actions through a more nuanced perspective. When talking to her sisters’ old childhood friend Laurie (played by Timothée Chalamet), she makes an extremely memorable speech explaining her decisions with the context of the expectations put upon women during the Victorian era.

Amy March does conform to gender roles, does revolve her life somewhat around men, and does make decisions that some would find shallow, but Greta does something I believe no male director could: she still manages to make the character strong-willed and relatable to a modern audience.

Despite the cast having many beautiful men and women, the movie never sexualizes them. Timothee Chalamet, who is this movie’s closest equivalent to a Bond girl, is made to seem desirable to the female gaze without being sexualized. The camera does pan on him in slow motion but it does not objectify him by doing this. The shot, which is from the perspective of his future love interest Amy, is the first time he is shown in the movie. It does not zoom in on any parts of his body, and unlike the Bond girls, he is fully clothed in Victorian attire.

Emma, 2020, directed by Autumn De Wilde

The 2020 adaptation of Emma wasn’t just the most beautifully directed and most historically accurate film I’ve seen directed by a woman… It was the most beautifully directed, most well-costumed regency era film I’ve ever seen. And trust me, I’ve watched a lot of period dramas. I don’t know why this genre tends to have more examples of the female gaze, but it does. These female directors manage to depict a time when women barely had any rights with more fascinating characters and costumes than most movies set in the present day have.

How do LGBTQ people and POC fit in within this binary of male and female gaze?

You may have noticed that most movies said to be in the “Male Gaze” are directed by cis white straight male directors and films said to focus on the “female” gaze tend to be directed by cis white female directors. So where do members of the LGBTQ community and POC fit into this binary set of labels?

According to Rachel Montpelier, writer for Woman and Hollywood, “People of color are approximately 40 percent of the U.S. population but were only 14.4 percent of directors, 13.9 percent of writers, and nine percent of studio heads. Like women, they fared best as actors, but are still not clearing proportionate representation. People of color comprised 27.6 percent of film leads and 32.7 percent of total actors.”

Another sad statistic is that GLAAD found that of the 118 films released from major studios in 2019, 22 (18.6 percent) included characters that were lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer (LGBTQ). Both of these marginalized groups have extremely low numbers of directors, actors, characters, and overall representation compared to their straight white counterparts.

Movies: the positive

Portrait of a Lady on Fire, directed by Celine Sciamma

Celine Sciamma is a queer French screenwriter and Director. Her movie Portrait of a Lady on Fire is at heart the perfect cross-over of the female gaze and female gays. The movie itself centers only on female characters in a large house on the sea. It is a women-loving-women romance that manages to avoid fetishizing their sexuality unlike the many W/W romances directed in a brutal way by straight men.

Blackkklansman, directed by Spike Lee

Black Klansman is a story about racial descrimination that avoids rose-colored glasses or the infamous White Saviour Trope. It is directed by a black man and I feel as if it is important for movies like these to be directed and written by people of color because a white director wouldn’t be able to depict all the nuances.

The Half of it, directed by Alice Wu

The Half of it is about a young Asian American girl coming to terms with her sexuality as well as culture. It has complex female characters as well as an Asian female writer. Instead of focusing on a romance like most coming of age movies tend to do the film focuses on the unlikely friendship between Ellie Chu and Paul Munsky who just so happen to like the same girl.

Final Thoughts

What do we hope to expect moving forward? How can movies include and appeal to audiences outside of the straight white male one? Moving forward, we hope and expect to see more diversity not just in front of the camera but behind the scenes as well.

Vance Cunningham • Nov 3, 2021 at 12:13 pm

How do films that explore sexuality while still using explicit imagery fit into this theory? ie Jodorowsky’s the Holy Mountain, which explores the spirituality of sex and the nude form, or Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, which critiques the inert sexual violence in society? Both are films directed by men, and they don’t feel exploitative at all.