The Life of Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

Over the summer, I picked up Malcolm X’s autobiography and read it from cover to cover. It was riveting and inspirational. His words were well-crafted and pulled you into the book. But afterwards, I thought it would be interesting to read the autobiography of the other most famous civil rights leader of the time, Martin Luther King Jr. While his book took much longer for me to become invested in, his words were also well crafted and he made his arguments about nonviolence well. Both autobiographies portray these leaders in a fascinating way that makes you feel like you’re right next to them as they go through their lives. While both were on the same side of the civil rights movement, they had vastly different beliefs about the best strategies for promoting social change. However, they also had respect for each other and near the end of his life, Malcolm X met and talked with King’s wife. In celebration of MLK day on January 16th, I have written a summary of his 366-page autobiography.

Before Civil Rights

Michael (later Martin) Luther King Jr. was born January 15th, 1929 to Michael (later Martin) Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams-King in Atlanta, Georgia. After a trip to Europe and Germany in 1934, King Sr. changed both his name and his son’s name to Martin in honor of Martin Luther, who started the protestant reformation. King (Jr.) credits his parents largely for his strong spirit and hatred for segregation. “In spite of her relatively comfortable circumstances, my mother never complacently adjusted herself to the system of segregation. She instilled a sense of self-respect in all of her children from the very beginning” (King 3).

At age 15 in 1944, King gave his first recorded speech in Dublin, Georgia for an oratorical contest, the speech was titled “The Negro and the Constitution” and won him the contest. That same year, he started his freshman year in Morehouse College. Then in 1948, after receiving his bachelors of arts degree in sociology from Morehouse, he entered Crozer Theological Seminary and was the first black man to be elected student body president. In 1951, he earned his bachelor of divinity degree from Crozer. Continuing down his educational journey, King entered Boston university in 1951, and in 1955 he would receive his doctorate in systematic theology at the age of 26.

In 1952, while King was in Boston University, he met Coretta Scott. Coretta was born on April 27th, 1927 in Heiberger, Alabama. She originally wanted to be a concert singer and was a mezzo-soprano. They were married on June 18th, 1953. He credits a lot of his strength during the civil rights movement to the strength of Coretta. “If I have done anything in this struggle, it is because I have had behind me and at my side a devoted, understanding, dedicated, patient companion in the person of my wife” (King 37).

In 1954, King officially became pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. He and Coretta moved to Montgomery, and on November 17th, 1955, their first child Yolanda was born. They had 4 children: Yolanda, Martin Luther King III, Dexter, and Bernice.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

On December 1st, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for violating segregation laws. Although she was not the first arrestee, her arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott since she was such a respected and loved person within the black community. Quickly, black organizations such as WPC (Women’s Political Council) circulated flyers promoting a bus boycott. The boycott became a huge success and spawned a newly formed protest group, Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), which elected King as president. Then, he and MIA developed plans to change Montgomery for the better. King was only 26 at the time.

The boycott was a large success immediately and King called the first few days inspiring and motivating. “They knew why they walked, and the knowledge was evident in the way they carried themselves. And as I watched them I knew there is nothing more majestic than the determined courage of individuals willing to suffer and sacrifice for their freedom and dignity” (King 55). The MIA then came up with a list of demands, such as courteous treatment by the bus operators guaranteed to black passengers, passengers seated on a first-come, first-served basis, and black bus drivers employed on predominantly black routes.

Black taxi companies had originally agreed to transport people participating in the bus boycott for the same fare that the buses had, which was 10 cents. However, after the first negotiation meeting with MIA and the city commission, King was tipped off that there was a law that limited the taxis to a minimum fare. So MIA organized a private carpool to continue to help people get to work.

The city commission then started making arrests on the boycott’s leaders and on January 26th, King was arrested and jailed for speeding, and then on January 30th, his home was bombed. Both these events rattled King but also made him determined to continue with the protest. King was released from jail on January 28th after paying a $14 fine. Montgomery city continued to try and stop the protests so on February 21st, 1956, King and MIA leaders were indicted for violating an antiboycott law. On March 22nd, King was found guilty and sentenced to 386 days in jail. But the protest continued and later on, King’s case was appealed.

Finally, on November 13th, the U.S. Supreme Court declared bus segregation laws unconstitutional. Then on December 21st, MIA voted to end the boycott. The boycott lasted for more than a year.

Atlanta Sit-in Movement

In 1960, King moved his family to Atlanta, North Carolina in order to participate in a lunch counter sit-in movement. Then on February 17th, he was arrested for allegedly falsifying his 1956 and 1958 Alabama state income tax returns. He was then sent back to Montgomery but was acquitted of tax evasion on May 26th. The obvious attempt to keep him from the sit-in movement failed and he and his family moved back to Atlanta.

Then on October 19th, King was arrested again for participating in the sit-in. He was arrested along with other participants but all charges ended up being dropped. However, King was held for allegedly violating probation for an earlier traffic offense and was transferred to Reidsville State Prison. Then Senator, later on, President, John F. Kennedy offered his assistance to Coretta King. After King’s attorney arranged his release from prison, King applauded Kennedy for his support. This probably won Kennedy the close election on November 8th for U.S. President since it caused many black voters to support him over Nixon.

While King was in jail, white and black leaders of the city brokered a deal that would desegregate the lunch counters in the fall. King and other leaders who had been in jail were upset with the delay of desegregation but ultimately agreed to the settlement.

Albany Movement

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which was headed by King, temporarily joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the Albany Movement in 1961 to help attract national attention to the Freedom Riders who were a group of mixed-race people who would ride the segregated buses in Albany, Georgia. They were protesting the segregation and mistreatment of black passengers.

During the movement, on December 16th, King as well as 700 other Albany protesters were arrested. King urged other protesters to not pay bail for anyone, not wanting to give the city money and wanting to fill up the jails with peaceful protesters and draw more attention to the Albany movement. 100 other protesters followed King in this example. However, King’s fine was paid by an unidentified person on July 12th.

On July 24th, there was an outbreak of racial violence where officials unleashed force against peaceful demonstrators. They brutally beat a pregnant woman and caned one of their lawyers. Onlookers, not demonstrators, then hurled bottles and stones at the police in retaliation. King temporarily halted mass demonstrations and for several days urged no retaliation. Stressing the need for nonviolence, he held a Day of Penance on July 25th.

Then on July 27th, King and other demonstrators were arrested after holding a prayer vigil in front of City Hall. He would stay in jail until August 10th, when their sentences were suspended. King agreed to call off the marches and return to Atlanta. The goals of the Albany movement were not met when King ended his direct involvement. King largely blamed the failure on the unclear and wide scope of the movement, which would later inform his leadership on other movements.

Birmingham Campaign

On April 3rd, 1963, SCLC and Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights launched a protest campaign in Birmingham, Alabama after Albert Boutwell won a run-off election for Police Commissioner against Eugene “Bull” Connor. However, Bull Connor refused to leave the office. They were protesting the city’s segregation system by putting pressure on stores during the Easter season, which is the 2nd biggest shopping season of the year. 9 days after the protests were launched, King was arrested after violating a state circuit court injunction against protests. 3 days later, President Kennedy once again called Coretta King to express concern and sympathy.

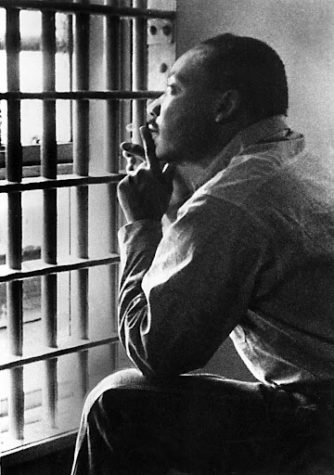

While in jail, King received news that 8 white clergymen in Birmingham wrote to King calling for an end to the demonstrations. In response, King wrote his famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail” in the small margins of newspapers and scraps of other papers. The letter, typed and double-spaced, ended up being 21 pages long. “There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience” (King 192).

On April 20th, King was released on bond after 8 days of imprisonment. SCLC then suggested the recruitment of young people and children into the protests. They invited students to attend after-school meetings at churches for training sessions and to learn the philosophy of nonviolent protest. Although there was a large amount of protest from adults, many of the children were excited to participate. “We found them eager to belong, hungry for participation in a significant social effort” (King 206).

Sadly, from May 2nd to 7th, Birmingham police would use fire hoses and dogs against protests called the “Children Crusade”. Over 1,000 children ended up being arrested. Because of this, on May 8th, mass demonstrations were suspended to open up negotiations with the Birmingham city commission.

On May 10th, the Birmingham city commission pledged: (1) The desegregation of lunch counters, rest rooms, fitting rooms, and drinking fountains, in planned stage within 90 days after signing (2) The upgrading and hiring of black people on a nondiscriminatory basis throughout the industrial community of Birmingham, to include hiring of black people as clerks and salesmen within 60 days after signing of the agreement–and the immediate appointment of a committee of business, industrial, and professional leaders to implement and area-wide program for the acceleration of upgrading and employment of black people in job categories previously denied to them (3) Official cooperation with the movement’s legal representatives in working out the release of all jailed persons on bond or on their personal recognizance (4) Through the Senior Citizens’ Committee or Chamber of Commerce, communications between black and white to be publicly established within two weeks after signing, in order to prevent the necessity of further demonstrations and protests.

Unfortunately though, after the pledges were announced, on May 11th, segregationists bombed the Gaston Motel where King was staying and the home of King’s brother, the Reverend A.D. King. Neither King nor his brother was hurt. But on May 13th, because of the bombing and other violent events, federal troops were sent to Birmingham. The troops forced Bull Connor out of the office and ended any more segregationist attempts at violence.

March on Washington

After the Birmingham Campaign, a March on Washington was proposed by A. Philip Randolph to unite all the anti-segregation movements happening across the country. People from every state came to DC for the demonstrations, there was also large participation from white churches as well. “It was white, and Negro, and of all ages. It had adherents of every faith, members of every class, every profession, and every political party, united by a single ideal. It was a fighting army, but no one could mistake that its most powerful weapon was love” (King 222). After drafting the speech, King read it over and then remembered a phrase he had used in a speech previously: “I have a dream”. He then decided to implement the phrase into his Washington speech and thus the iconic and most famous “I Have a Dream” speech was born. About 250,000 demonstrators showed up, it was a historic moment for the civil rights movement. But contrary to popular belief, it was not the end of the movement at all.

Nobel Peace Prize

On December 10th, 1964, Martin Luther King Jr received the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway. King and his wife toured Scandinavia and he gave a lecture at the University of Oslo. He was very impressed with Europe’s beliefs on the civil rights movement and believed that the U.S.’s continued segregation system appalled other nations and would one day be the U.S.’s undoing.

King also dedicated his prize to the movement as a whole, rather than individual people. “In the final analysis, it must be said that this Nobel Prize was won by a movement of great people, whose discipline, wise restraint, and majestic courage have led them down a nonviolent course in seeking to establish a reign of justice and rule of love across this nation of ours.” (King 257).

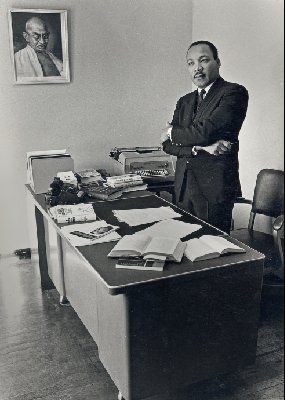

Gandhi

Much of King’s personal philosophy about nonviolence comes from Mahatma Gandhi, who led a similar campaign in India and successfully brought down British rule over India. King admired the man so much that he hung a picture of Gandhi above his dining room table.

On February 3rd, 1959, King, Coretta, and Dr. L.D. Reddick, embarked on a trip to India. First, they would stop at Paris, then India. They had dinner with India’s Prime Minister at the time, Nehru. This visit inspired King, “I returned to America with a greater determination to achieve freedom for my people through nonviolent means. As a result of my visit to India, my understanding of nonviolence became greater and my commitment deeper” (King 134).

Vietnam

When the Vietnam war started, King did not share his opinion on the subject. But after agonizing and thinking about it for a long time, he finally started openly denouncing it and speaking against it. “Today, young men of America are fighting, dying, and killing in Asian jungles in a war whose purposes are so ambiguous the whole nation seethes with dissent. They are told they are sacrificing for democracy, but the Saigon regime, their ally, is a mockery of democracy and the black American soldier has himself never experienced democracy” (King 333). Many people criticized King for his opposition to the Vietnam war, saying that he should stay involved in civil rights in America and that he was “getting out of his depth”. But King continued his stance against the Vietnam war and continued to challenge other civil rights organizations to also take a stand.

Mississippi

On July 21st, 1964 King arrived in Mississippi to assist in the civil rights movement after 3 civil rights workers were reported missing after being arrested in Philadelphia on June 21st. The campaign titled Mississippi’s “Freedom Summer” was a large-scale voter drive that wanted to increase the number of registered black voters in Mississippi.

However, the Ku Klux Klan and members of state and local law enforcement violently resisted the Freedom Summer volunteers, which led to national news coverage of beatings and murders that occurred. This media coverage drew more attention to the civil rights movements and voter discrimination, which led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Sadly, Freedom Summer was considered a failure since it did not get many more black voters registered.

Selma

In 1965, King began working with people in Selma, Alabama in another voting rights movement. But on February 1st, King along with 200 other demonstrators was arrested after a march. Afterward, on February 26th, Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by police during another march in Marion, Alabama. Then on March 7th, voting rights marchers are beaten by police at Edmund Pettus Bridge. The violence against protesters seemed to continuously escalate the more demonstrations occurred.

King left jail on February 5th and then organized a march from Selma to Montgomery, a 51-mile walk. The march concluded with an address from King, but hours afterward, Klan night riders killed Viola Gregg Liuzzo while she was transporting marchers back to Selma. King’s speech included inspirational and strengthening words to help the marchers continue on their way and keep fighting. “We are not about to turn around. We are on the move now. Yes, we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us. We are on the move now. The burning of our churches will not deter us. We are on the move now. The bombing of our homes will not dissuade us. We are on the move now. The beating and killing of our clergymen and young people will not divert us. We are on the move now.” (King 285)

Los Angeles

The continued and escalating violence against movements like in Selma and Mississippi led to the outbreak of widespread racial violence in Los Angeles which resulted in 30 deaths. King went to Los Angeles after the violence at the invitation of local groups on August 17th, 1965. It is important to note that killings were largely committed by police and not the rioters. “The violence of poverty and humiliation hurts as intensely as the violence of the club. This is a situation that calls for statesmanship and creative leadership, of which I did not see evidence in Los Angeles.” (King 295)

Final Days

A year before he died, King launched a campaign to fight poverty in the U.S. Not just for black communities but also for white communities as well. This campaign did not gain much news media since it was in its infancy when King was assassinated. On April 3rd, 1968, King gave his last speech at Bishop Charles J. Mason Temple in Memphis. “Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter” (King 366). The next day, April 4th, King was assassinated at Lorraine Motel. The nation grieved him and he went down in history as possibly the most influential and famous civil rights leader in the world.

Mohammed Salim Ali • Nov 21, 2024 at 7:13 am

I was searching a source that can help me in my school projects and I actually got the best source with the information that I want. Thank you so much for your help .

jordan • Feb 25, 2024 at 10:18 am

this is interesting love it.

jordan • Feb 25, 2024 at 10:17 am

this helped me on a project thank you.