The Greatest Film Never Made: Jodorowsky’s Dune (Part Three)

Part Five: Legacy

The legacy of Jodorowsky’s Dune began where it ended, with the studios. As stated earlier, Jodorowsky sent out a proof of concept book, the Dune Book, with all of the drawings and a final script, to every major US studio. They kept those books, and have used the concept drawings ever since in sci-fi films such as Flash Gordon, Star Wars, Contact, The Terminator, The Matrix, Blade Runner, and most significantly in Alien. But Alien did more than just take inspiration from the Dune Book’s designs, it took Dune’s entire crew. VFX artist Dan O’Bannon wrote the original story for Alien, titled “Memory,” prior to working on Dune. After Dune fell through, he returned to Los Angeles and began rewriting the story into what became the original screenplay for Alien. H.R. Giger is particularly famous for his work on the film, having first inspired the Alien, as well as having created some original concept art for the film. Moebius and Chris Foss were also hired to provide concept art, and Ridley Scott, who has his own failed Dune project (more on that later), was hired to direct the film. It was a massive success, grossing over $200 million, and nominated for multiple Oscars, winning the award for Best Visual Effects. The 2012 Alien prequel, Prometheus, also borrowed directly from Dune’s concept art in the form of the Harkonnen Castle, showing that the influence of Jodorowsky’s Dune has yet to fade away.

The collapse of the project was devastating for Jodorowsky. He moved to India for a time and directed the film Tusk, which is relative to the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special in terms of how bad it is and how badly the creator wants to forget its existence. He did make a comeback with his 1989 psychological horror film Santa Sangre, which depicts an insane mother who forces her son to act as her hands after losing her own. Unfortunately, due to the film’s NC-17 rating, which was probably put in place due to the frequent and extremely violent murders depicted, it didn’t do very well at the box office. Jodorowsky needed to make some money, and agreed to direct the film The Rainbow Thief with no creative control. He described it as the worst experience of his life, and only strengthened his hatred of the studio system.

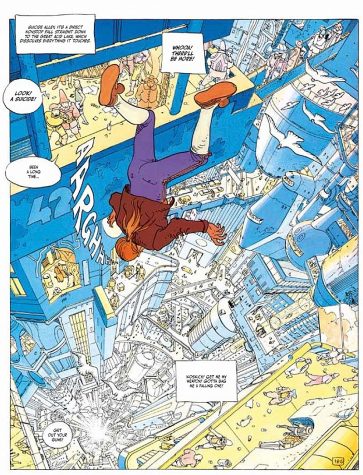

Jodorowsky also has a long career writing graphic novels, which he started after the production of Tusk. His first success came when he partnered with Dune storyboard artist Moebius to create the sci-fi graphic novel “The Incal.” Pieces of the original art from the Dune storyboards and designs by Moebius were used throughout the book, and it was a massive success. It is considered to be one of the greatest graphic novels of all time, and launched a series of graphic novels set in his “Jodoverse.”

In the early 2000s, he attempted to make a sequel to El Topo titled Children of El Topo, perhaps a nod to the Dune sequel Children of Dune. The film was tangled up in a lawsuit between Alan Klein and Jodorowsky, and was eventually abandoned. Alan Klein, the Beatles’ manager who had bought the distribution rights to Jodorowsky’s films, still held a grudge against the filmmaker for abandoning the Story of O project without telling him. He had locked down El Topo and The Holy Mountain, refusing to release them on home video or in theaters anywhere. For years, the film was only available to watch at midnight art house theaters via bootlegs, which only strengthened the film’s mystical appeal. The films were finally released in 2007, and are now widely available. Jodorowsky, who is 91 years old, continues to make films. His latest projects, The Dance of Reality and the autobiographical Endless Poetry, have received wide critical acclaim. They are much more retrospective, exploring deep philosophical themes without the extreme violence and shock value of his earlier works.

Part Six: After Jodorowsky

Of course, the end of Dune for Jodorowsky wasn’t the end of Dune as a film. The movie world changed in 1977 with the release of the sci-fi blockbuster Star Wars. Suddenly, every studio wanted to make as many sci-fi films as they possibly could to bank off of its massive success. Producer Dino De Laurentis had bought the rights to Dune after the Jodorowsky project fell through, and began working with author Frank Herbert writing an original script. Alien director Ridley Scott was hired for the project, and began writing an entirely new script after scrapping Herbert’s. What became of Herbert’s script is unknown, but it was likely used as a baseline for the David Lynch Dune project, with which Herbert was very involved. Artist H.R. Giger was again hired for Dune after working on Alien with Scott, and created several new concept drawings. The team was building large-scale setpieces and designing the costumes when tragedy shut down the project for good. Ridley Scott’s brother Frank died in 1980, forcing Ridley into an extreme depression. He was anxious to make a film immediately, hoping to use his work as a coping tool. He abandoned Dune after realizing how much time the project would need before he could start shooting, and decided to pick up a script he had turned down earlier that year titled “Dangerous Days.” That script eventually turned into the 1982 classic Blade Runner. Dune changed hands once again.

Producer Dino De Laurentis then handed the project off to his daughter, Rafaella, to produce the film, following her success with the movie adaptation of Conan the Barbarian. She hired director David Lynch to head the project after watching a midnight screening of The Elephant Man. David Lynch had actually been approached to direct the Star Wars sequel Return of the Jedi, but had turned it down. He agreed to do the Dune project, however, because it was less mainstream of a film. Lynch began working on a script closely with Frank Herbert, and principal photography began in 1983. Dune was finally being filmed.

The project was extremely expensive, costing the studio over $40 million. It was mainly shot on location in deserts, with soundstages used for the extensive model work and visual effects. Initially, Lynch had total creative control. Rafaella De Laurentis trusted his vision, until she began to see what he was creating. She had not seen Lynch’s earlier film, Eraserhead, which was a midnight movie in it’s own right, and much less mainstream that The Elephant Man. Universal Studios went from accepting the 3 hour runtime to demanding a 2 hour cut. Lynch was forced to condense his experimental and artistic vision dramatically, sacrificing exposition, character development, and pacing to squeeze the immense story into a little over 2 hours. Finally, on December 14, 1984, a film adaptation of Dune was released into theaters.

Jodorowsky describes his experience of seeing the film for the first time as a painful one. At first he was reluctant to go see it, saying that Dune had been his dream and it made him ill to think of someone else doing the project. “And then they start to show the picture, and step by step, I was so happy, so happy, so happy because it was a sh*tty picture.” The rest of the world seemed to agree. Dune grossed $30 million over its theatrical release, losing $10 million and officially making it a flop. It was panned by critics, with Siskel and Ebert naming it the most disappointing film of the year. It was overcomplicated, boring, lacking in action, full of cheesy dialogue, and wasn’t faithful to the book at all. David Lynch himself hated the film, and refused calls to make a director’s cut. When an extended TV cut was released without his oversight, Lynch refused to have his name appear on the film. The director’s credit went to Alan Smithee, the pseudonym used by Hollywood directors if they want to disavow their projects, and the writer’s credit went to Judas Booth, a cross between Judas, the biblical figure who betrayed Jesus, and John Wilkes Booth, the man who assassinated President Lincoln. While the film has since gained a cult following, it is still widely regarded as one of the worst films ever made. After almost 20 years, Dune had been made into a movie, and was a failure. Maybe Jodorowsky was right, “Dune, nobody can do it. It’s a legend.”